Leonardo da Vinci Last Supper | Location | Opening Hours Tickets | Authorizations

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” at Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan

Leonardo da Vinci “Last Supper”

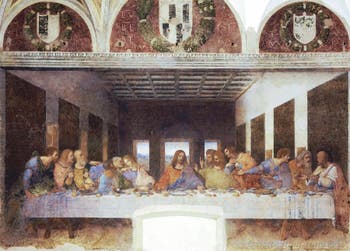

Fresco - Tempera on Coating (460 x 880 cm) 1493/1494 - 1498

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” is one of his most famous and admired works worldwide; it was a total success among his contemporaries.

Leonardo da Vinci became famous thanks to this astonishing fresco depicting the “Last Supper”, the last meal of Jesus with his disciples.

King Louis XII of France was so moved by this image of the “Cenacolo”, Leonardo da Vinci's Cenacle, that he asked that it be removed from the wall of the monastery refectory to transport it to France.

But this was an impossible operation, as the work is particularly fragile because it was painted in tempera on plaster, and its attempt to move would have caused its destruction.

The choice of the crucial moment of the “Last Supper” and the genius of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” The genius of Leonardo da Vinci in this “Last Supper” lies in the precise moment he chose to show and in the way he illustrated it.

The moment of Leonardo's “Last Supper” is not that of the Eucharist usually represented in his time, but the moment when Jesus said to his apostles: “Truly, I say to you, one of you will betray me.”

Astonishment, anger, disbelief, fear, dismay, and denial are the apostles' reactions to these shocking words, telling them that one of them is about to betray Him to whom they have decided to devote their lives.

Only one apostle behaves differently from his companions, Judas.

He only expresses his fear of being discovered by stiffening back in his chair and clutching the bag containing 30 pieces of silver, the price of his treason.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” Leonardo da Vinci introduces a novelty here compared to the Last Suppers painted before him.

Judas was represented sitting on the other side of the table, opposite and separated from the other apostles; Leonardo da Vinci thought that this positioning “outside” would break the surging wave of emotions and reactions that he wanted to stage.

He, therefore, preferred to break the iconographic rules in force and place Judas among the other apostles.

The dramatic intensity of the declaration of treason is at its peak in this work by Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” The apostles are upset, disoriented, helpless, and angry, and some foresee this villainy's dramatic consequences.

The revelation of the sneaky presence of evil plunged them into anxiety about a future full of threats.

All the genius and creative power of Leonardo da Vinci are expressed here.

We are at the table with them, facing them; the drama is taking place before us, and we are as upset as they are.

The representation of Jesus in Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper”

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” Amid this extreme agitation of the apostles, Jesus is calm and thoughtful; he does not rebel; he surrenders; he calmly accepts the imminence of his destiny, the betrayal, the humiliation and the death that will follow.

Christ's mouth is still ajar; his words still ring in the ears of the apostles.

Christ is not looking at his apostles; he is not looking at us; he is looking at the bread and wine on the table.

Jesus is already in the attitude of the man of pain; he opens his arms to his destiny as if to welcome and embrace him.

His arms are open, even for the person who betrayed him.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” By painting Jesus in this attitude, Leonardo da Vinci indicates the Eucharist's time; Christ's hands that accompany his gaze present us with the bread and wine of salvation.

The representation of the hands of Jesus is another genius feature of the painter; he positions them in opposite directions, one with the palm facing up while the other is facing the table.

By reversing the position of the hands, Leonardo da Vinci illustrates at once the two moments of the holy sacraments, that of the consecration when Jesus takes the bread and wine and that of Communion when he offers them as his body and the blood of the covenant.

These two hands with opposing gestures also allow Leonardo da Vinci to present Jesus as the Sovereign of the Universe, opening his arms to welcome or to repel: he is the priestess, king and judge at the same time, according to Saint Thomas Aquinas.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” Saint Thomas Aquinas was Dominican, as were Santa Maria delle Grazie monks, where Leonardo da Vinci painted this “Last Supper” to decorate their refectory.

Leonardo da Vinci remained for four years amid these monks and listened to their advice.

We can imagine his conversations with Dominican monks throughout the maturation of his creation, the reflections they had to exchange and that he took into account to represent the figure of Jesus and the attitude of each of the apostles.

By thoroughly analysing the apostles' character, history, and career and what motivated them to become followers of Jesus, Leonardo da Vinci could conceive and represent their respective reactions to the fateful announcement of the betrayal.

This announcement is an explosion because that is what it is all about, like a clap of thunder in the silence and peace of a serene sky, in the peace of mind of the apostles whose world is about to change.

How did Leonardo da Vinci manage to represent the hustle and bustle of the apostles in a harmonious and orderly manner?

All the genius of Leonardo da Vinci was used here to transmit to us the devastating impact of the words of Jesus on his apostles.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” For four years, the painter studied, questioned, doubted, sought, drew sketches, destroyed them and started over again until he found the solutions that satisfied him to create his masterpiece.

He had to show the shock wave that hits the apostles and makes them startle, growl, and pounce off the table.

How can we represent this in a powerful, harmonious and orderly way so that the viewer's eye does not get lost in a profusion of such diverse attitudes, expressed by all these hands, gestures, faces and bodies vibrating with indignation?

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” How do we represent 12 characters along this table while expressing all the dramatic intensity of the moment when Jesus announced the betrayal?

How can we show the extreme agitation of the apostles while Jesus remains perfectly calm without this being able to break the dynamic of the action to be represented?

To do this, Leonardo da Vinci divided the scene into four groups of three apostles, ensuring that the viewer did not face four unrelated paintings, given the significant differences in attitudes from one end of the table to the other.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” To begin with, the artist extended the space of the refectory room by creating a plunging and profound perspective, bringing together all the parts of the fresco towards a central vanishing point: the face of Christ.

The visual effect of this perspective is such that the eye can only follow it and cannot remain fixed on this or that part of the fresco; it is drawn to the centre where the main character, Jesus, sits.

Leonardo da Vinci further accentuates the visual power of the central point of the perspective by positioning Jesus in front of a window, the sole source of light.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” The lower white zone did not appear in the original work; it is the trace of a door pierced in the 17th century in an imbecile way into the refectory wall to access the kitchens!

This white area carved out the feet of Christ and part of the tablecloth.

To add to the visual effect of this perspective in the spatial organisation of the “Last Supper”, Leonardo da Vinci painted three lunettes above the fresco, depicting the coats of arms of the Sforza family: a large central lunette surrounded by two smaller lunettes.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” It is another sign of Leonardo da Vinci's genius that we notice here: he used these glasses both to “order” his groups of apostles and to “isolate” Judas.

The groups of three apostles on the left and right are precisely placed under the two external lunettes, and Jesus and the other two groups are painted under the central lunette, while the head of Judas is placed under the column separating the left outer lunette from the central lunette.

It was not only Leonardo da Vinci who “extracted” Judas from the group; it was Judas himself who separated himself from his group by retreating at the announcement of his betrayal.

The traitor “comes out” of the lunette and denounces himself in our eyes by distancing himself from the community of disciples. Now, he is no longer part of it.

The apostles Bartholomew, James, son of Alpheus and Andrew

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” At the far left of the Last Supper appears the first group of three apostles: Bartholomew, James, son of Alpheus, and Andrew.

Bartholomew is at the end of the table, standing, leaning forward, his right hand clasps the edge of the table while the other is resting on it; he is in an almost aggressive attitude, he is ready to pounce on the traitor and at the same time he is leaning forward as if he hoped to be able to hear the statement that disturbed him so much.

At the centre of this group is James, the son of Alphaeus or James the Minor, who is called “brother of Jesus” in the Gospel of Saint Mark.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” This name of brother, James, does not owe it to a family link but simply to his physical resemblance to Jesus.

Leonardo da Vinci did not fail to represent him with a high and broad forehead, a straight nose and a garment identical and of the same colour as that of Jesus, but paler.

James puts his right hand on Andrew's shoulder while his left-hand touches Peter's.

The gestures used by Leonardo da Vinci show us the links between the apostles and visually connect this first group of three apostles to the next group.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” Andrew, for his part, raises his hands, showing his palms in a gesture of indignation and repulsion.

While James' face is entirely painted in profile, Andrew's is shown three-quarters of the way he looks at Judas' neck; it is to him that the repulsion of his gesture is directed.

Andrew also shows his hands in a gesture that means that they are clean, that he is not the traitor, and that he is innocent, while Judas' hand is closed, clasped around the purse that contains the money for his treason.

The apostles Judas, Peter, and John

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” The next group of apostles shows Judas, isolated and withdrawn, with a dark face as if he were already in the shadow of himself, deprived of light, while Peter and John are close behind him.

Peter puts his hand on John's shoulder, and their heads lean towards each other.

Peter asks John if he knows anything more about this betrayal, and Judas seems to want to listen to what he is saying.

John asked Jesus the question at Peter's request, but that is not what matters at this crucial moment, represented here by Leonardo da Vinci, who is content to announce what will follow.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” While he puts his hand on John's shoulder, Peter is still holding the knife from his meal in the other, in a gesture reflecting his nervousness and anger, just like the features of his face, while John's almost feminine features express only sadness.

John is the only apostle who seems to remain calm at the announcement of the betrayal, yet his crossed and clasped hands betray his sadness, affliction, and pain.

He knows what will happen is inexorable, and nothing can prevent it.

John was Jesus' most loved apostle and sat beside him with the same drape over his left shoulder.

Leonardo da Vinci represented John as a double of Jesus, his eyes closed, his head bowed, and his clothes identical to Jesus's, but with inverted colours.

When Jesus found himself on the cross, he asked John to take care of the Virgin Mary.

The apostles Matthew, Jude Thaddaeus, and Simon

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” To the right of the fresco, at the other end of the table, Simon parallels Bartholomew; Simon talks with Matthew and Jude, also called Thaddeus.

Simon and Jude comment on the announcement of Jesus.

Simon does not seem surprised by the announcement of the betrayal, while Jude seems perplexed and arguments, as shown by his hand raised upwards, while the other, placed on his back on the table, reflects his nervousness.

Next to them, Matthew's questions show his disbelief at the same time as his anxiety by turning to his two companions and reaching out to Christ to indicate that they are talking about him.

An obvious one, certainly, but also a superb idea by Leonardo da Vinci on a visual level: Matthew's hands, like Simon's, are on the same horizontal line to direct and return the viewer's gaze to the centre of the scene and to connect this group of apostles to the previous one.

The apostles Thomas, James the Greater, and Philip

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” The last group of apostles, directly to Christ's left, represents Thomas, James the Great, and Philip from left to right.

James the Great, at the centre of the group, extends his arms wide in a gesture that means he has nothing to blame himself for and is also ready to help discover the traitor.

James' face is tense; his eyes are hard, dark, and aggressive.

He wants to fight with whoever is going to betray Jesus.

The way James the Great opens his arms forms a cross with his body, the cross that would become the symbol of Christianity.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” Behind James the Great, we see Thomas's questioning face and his hand raised to ask Jesus for permission to ask him a question.

His finger has a double meaning because it is also directed to heaven, as if Thomas's question was addressed to God, who knows all the truth.

Philip bends to Jesus, imploring, with both hands on his chest, to say, “It's not me,” as Goethe analysed when he saw the “Last Supper”.

Philip's face expresses amazement and distress, and the gesture of his hands can also mean acceptance of the divine will, even if he cannot yet understand the coming mystery of Christ's passion.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” The hands on the chest were often used as a sign of submission in iconography during the time of Leonardo da Vinci.

Leonardo da Vinci's “Last Supper” A masterpiece unique in the world

Leonardo da Vinci showed extreme care to translate the symbolism of this Last Supper in all its theological depth, to reproduce as faithfully as possible the different characters of the apostles in the expression of the faces and attitudes of each one.The months and years of research before succeeding in defining and reproducing each of them are among the essential creative elements of this undisputed masterpiece of the artist.

An exceptional work, unparalleled, which had such an impact in its time that no painter worthy of the name anymore dared to paint a Last Supper according to the criteria in force before the one painted by Leonardo da Vinci.

It is a unique masterpiece that you must see on-site to feel all the intensity and emotion it transmits to us.

Leonardo da Vinci Last Supper | Location | Opening Hours Tickets | Authorizations

Back to Top of Page